About the Healthy Life Trajectories Initiative (HeLTI)

The Healthy Life Trajectories Initiative (HeLTI) is an international consortium formed as a ten-year initiative funded jointly by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Department of Biotechnology (India), Medical Research Council (South Africa) and the National Natural Science Foundation (China), and in collaboration with the World Health Organization (WHO) to address the increasing burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) around the world.

The Healthy Life Trajectories Initiative (HeLTI) is an international consortium formed as a ten-year initiative funded jointly by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Department of Biotechnology (India), Medical Research Council (South Africa) and the National Natural Science Foundation (China), and in collaboration with the World Health Organization (WHO) to address the increasing burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) around the world.

HeLTI uses the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) approach, which is based on the notion that environmental factors interact with genes during conception, fetal life, infancy and early childhood, and that this programming affects the individual’s health later in life. Harmonized studies are implemented in four countries to test if an integrated continuum of care intervention starting pre-conception and continued across the pregnancy, infancy and childhood phases will reduce childhood adiposity, impact maternal health and ultimately improve child development.

In each of these countries, longitudinal multi-sectoral lifestyle interventions will be initiated during the preconception phase and then tailored to respond to the specific needs of the family during pregnancy, infancy and early childhood. Time sensitive interventions will aim, amongst others, at promoting healthy pre-pregnancy behaviors, optimizing maternal health, preventing maternal depression, enhancing home environment, supporting exclusive breastfeeding, encouraging child health behaviors, and promoting nurturing parental care. Recognizing the context and specificities, including the diversity of lifestyle patterns across populations, the four studies are designed to meet the respective needs of the local population but yet are prospectively harmonized through the development of common research, measurements, and data collection protocols to allow comparative evaluation.

Watch the HeLTI short video and learn more about us!

Background

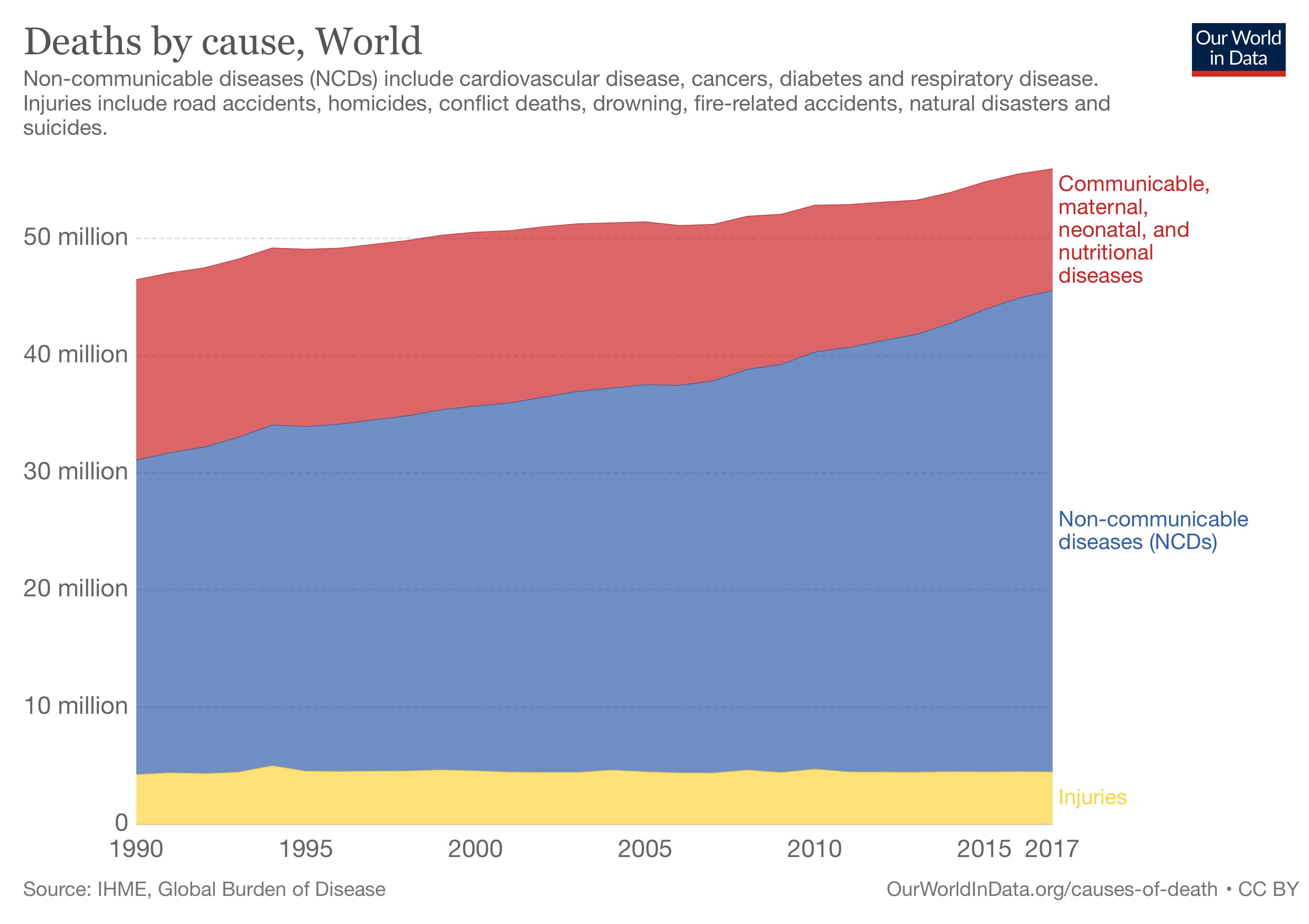

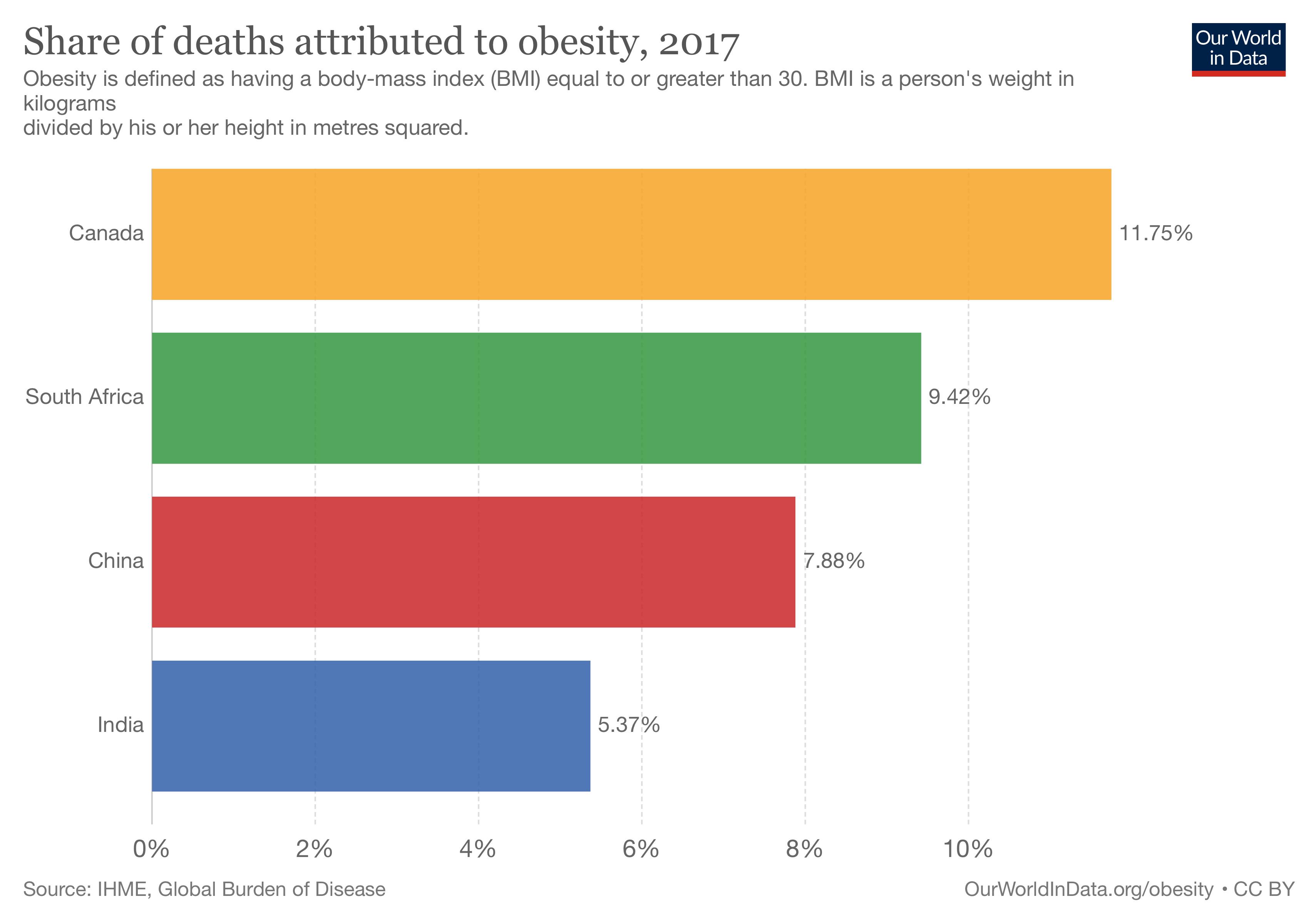

The rising problem of obesity and non-communicable diseases

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs), including cardiovascular disease (CVD), type 2 diabetes mellitus and mental illness - especially depression - are major global contributors to premature death and disability1,2. However, their prevalence and trends vary between countries. In Canada, overweight and obese states are found in 70% of men and 60% of women, and are creeping into younger age groups, thus forecasting serious economic, societal and personal consequences. Today, over 25% of children in Canada are overweight or obese.

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs), including cardiovascular disease (CVD), type 2 diabetes mellitus and mental illness - especially depression - are major global contributors to premature death and disability1,2. However, their prevalence and trends vary between countries. In Canada, overweight and obese states are found in 70% of men and 60% of women, and are creeping into younger age groups, thus forecasting serious economic, societal and personal consequences. Today, over 25% of children in Canada are overweight or obese.

While NCDs were previously most common in high-income western countries and rare in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), they are now plateauing or falling in the former and rapidly increasing in the latter1–3. There are about 166 million people with diabetes in China and India combined (40% of the world’s total). Depression is the leading neuropsychiatric cause of disease burden globally and in LMICs4, and by 2020 it is projected to be the second leading cause of burden of disease5.

Rates of antenatal and postnatal depression in LMICs are higher than in high-income countries, with estimates of 16% and 19% respectively6. Adiposity increases NCD risk, and the epidemics of CVD and diabetes in LMICs have emerged with greater economic development, urbanisation, obesogenic lifestyles, and high and rising rates of overweight and obesity (OWO) 7-9 . OWO affects 30-40% of Chinese adults and South African men, and over 60% of South African women. Prevalence is lower in India (about 20%), where underweight remains more common, though high rates are present in urban and high socio-economic groups. OWO is not the only driver for rising trends in NCDs10. While OWO prevalence is lower in LMICs than in high-income countries, NCD rates are comparable or higher. High rates of diabetes and hypertension are reported even in rural areas and at relatively low BMI11–13.

Rates of antenatal and postnatal depression in LMICs are higher than in high-income countries, with estimates of 16% and 19% respectively6. Adiposity increases NCD risk, and the epidemics of CVD and diabetes in LMICs have emerged with greater economic development, urbanisation, obesogenic lifestyles, and high and rising rates of overweight and obesity (OWO) 7-9 . OWO affects 30-40% of Chinese adults and South African men, and over 60% of South African women. Prevalence is lower in India (about 20%), where underweight remains more common, though high rates are present in urban and high socio-economic groups. OWO is not the only driver for rising trends in NCDs10. While OWO prevalence is lower in LMICs than in high-income countries, NCD rates are comparable or higher. High rates of diabetes and hypertension are reported even in rural areas and at relatively low BMI11–13.

Developmental origins of obestiy and NCDs

Intrauterine and early infancy exposures appear to influence a person’s risk of adult-onset chronic diseases, including cardiometabolic disorders, which is the core premise of the developmental origins of health and disease (DOHaD) hypothesis. Poor maternal nutrition in pregnancy can lead to fetal growth restriction and predispose to cardiometabolic diseases in adulthood (e.g. diabetes, hypertension). Low birth weight and in utero exposure to maternal diabetes, hypertension and obesity are each associated with elevated blood pressure, plasma glucose, insulin, and lipid concentrations in children at age 5 years14–16. These childhood risk markers are known to track into adult life and predict disease17,18.

Some well-studied exposures in pregnancy or early infancy have long-term consequences, known as developmental programming. These include: 1) maternal obesity; 2) gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM); 3) maternal smoking; 4) formula feeding in infancy; and 5) fetal/infant exposure to stress or parental depression. High levels of maternal stress/anxiety have been linked to increased risk for anxiety disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder, increased body mass index (BMI), insulin resistance, reduced cognitive performance, 3 schizophrenia and altered function of stress response systems in children; and in many cases these effects are sex-specific19,20.

DOHaD research also suggests that NCD risk is not only influenced by exposure to ‘load’ factors such as adult obesity and inactivity, but also by the ‘capacity’ of key metabolic tissues, which is acquired during early development21-23. Cohort studies have shown that higher BMI at 1-2 years of age is associated with a lower CVD and diabetes risk in adult life 24,25 , suggesting that, like fetal life, infancy is a period of continuing developmental vulnerability. In contrast, BMI gain after this time (childhood, adolescence and adult life) even in the absence of frank obesity is associated with increased NCD risk24-26. In all populations, the highest risk of CVD and diabetes, and the most adverse cardio-metabolic risk markers, are in men and women who were light and thin at birth and in infancy, but gained the greatest BMI as children or adults24,25. It is now known that early life exposures other than undernutrition lead to metabolic programming, and that disorders other than CVD and diabetes have early life origins.

Mechanisms of programming

Parental anxiety and depression can impact the quality of infant and child care, which is integral to improving cognitive function and other health outcomes later in life. Children who receive a low quality of care are more sensitive to the effects of stress and display more behavioral problems. These poor outcomes are especially pronounced in children who have a genetic predisposition to environmental influence. The early environment can also impact brain structure. Early deprivation (neglect, maltreatment, abuse, etc.) can lead to changes in the shape and volume of various brain structures in children and adults. Regions that are involved in learning and memory, as well as communication between different parts of the brain are particularly sensitive27.

1. Wang, H. et al. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. The Lancet 388, 1459–1544

2. Ng, M. et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 384, 766–81 (2014).

3. Worldwide trends in diabetes since 1980: a pooled analysis of 751 population-based studies with 4·4 million participants. The Lancet 387, 1513–1530

4. Patel, V., G, S., N, C., S, K. & R, A. Packages of care for depression in low- and middle-income countries., Packages of Care for Depression in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. PLoS Med. PLoS Med. 6, 6, e1000159–e1000159 (2009).

5. Mathers, C. D. & Loncar, D. Projections of Global Mortality and Burden of Disease from 2002 to 2030. PLOS Med. 3, e442 (2006).

6. Fischer, J. WHO | Prevalence and determinants of common perinatal mental disorders in women in low- and lower-middle-income countries: a systematic review. WHO Available at: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/90/2/11-091850/en/. (Accessed: 9th February 2017)

7. Angkurawaranon, C., Jiraporncharoen, W., Chenthanakij, B., Doyle, P. & Nitsch, D. Urbanization and non-communicable disease in Southeast Asia: a review of current evidence. Public Health 128, 886–895

8. Trends in adult body-mass index in 200 countries from 1975 to 2014: a pooled analysis of 1698 population-based measurement studies with 19·2 million participants. The Lancet 387, 1377–1396

9. (NCD-RisC), N. R. F. C. Worldwide trends in blood pressure from 1975 to 2015: a pooled analysis of 1479 population-based measurement studies with 19·1 million participants. The Lancet 389, 37–55 (2017).

10. Dagenais, G. R. et al. Variations in Diabetes Prevalence in Low-, Middle-, and High-Income Countries: Results From the Prospective Urban and Rural Epidemiological Study. Diabetes Care 39, 780 (2016).

11. Liu, X. et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, control of type 2 diabetes mellitus and risk factors in Chinese rural population: the RuralDiab study. Sci. Rep. 6, 31426 (2016).

12. Malaza, A., Mossong, J., Bärnighausen, T. & Newell, M.-L. Hypertension and Obesity in Adults Living in a High HIV Prevalence Rural Area in South Africa. PLOS ONE 7, e47761 (2012).

13. Raghupathy, P. et al. High prevalence of glucose intolerance even among young adults in south India. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 77, 269–279 (2007).

14. Tam, W. H. et al. Glucose Intolerance and Cardiometabolic Risk in Adolescents Exposed to Maternal Gestational Diabetes. Diabetes Care 33, 1382–1384 (2010).

15. Boney, C. M., Verma, A., Tucker, R. & Vohr, B. R. Metabolic Syndrome in Childhood: Association With Birth Weight, Maternal Obesity, and Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Pediatrics 115, e290–e296 (2005).

16. Krishnaveni, G. V. et al. Exposure to maternal gestational diabetes is associated with higher cardiovascular responses to stress in adolescent Indians. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 100, 986–993 (2015).

17. Bao, W., Threefoot, S. A., Srinivasan, S. R. & Berenson, G. S. Essential hypertension predicted by tracking of elevated blood pressure from childhood to adulthood: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Am. J. Hypertens. 8, 657–665 (1995).

18. Joshi, S. M. et al. Tracking of cardiovascular risk factors from childhood to young adulthood — the Pune Children’s Study. Int. J. Cardiol. 175, 176–178 (2014).

19. Glover, V. Annual Research Review: Prenatal stress and the origins of psychopathology: an evolutionary perspective. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 52, 356–367 (2011).

20. Dancause, K. N. et al. Disaster-related prenatal maternal stress influences birth outcomes: Project Ice Storm. Early Hum. Dev. 87, 813–820 (2011).

21. Barker, D. J. P. & Godfrey, K. M. in Nutritional Health (eds. Wilson, T. & Temple, N. J.) 253–268 (Humana Press, 2001). doi:10.1007/978-1-59259-226-5_16

22. Hales, C. N. & Barker, D. J. P. Type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus: the thrifty phenotype hypothesis. Int. J. Epidemiol. 42, 1215–1222 (2013).

23. Wells, J. C. K., Pomeroy, E., Walimbe, S. R., Popkin, B. M. & Yajnik, C. S. The Elevated Susceptibility to Diabetes in India: An Evolutionary Perspective. Front. Public Health 4, (2016).

24. Barker, D., C, O., E, K. & Jg, E. Growth and chronic disease: findings in the Helsinki Birth Cohort. (2009).

25. Bhargava, S. K. et al. Relation of serial changes in childhood body-mass index to impaired glucose tolerance in young adulthood. N. Engl. J. Med. 350, 865–875 (2004).

26. Adair, L. S. et al. Associations of linear growth and relative weight gain during early life with adult health and human capital in countries of low and middle income: findings from five birth cohort studies. The Lancet 382, 525–534 (2013).

27. Teicher, M. H. & Samson, J. A. Childhood maltreatment and psychopathology: A case for ecophenotypic variants as clinically and neurobiologically distinct subtypes. Am. J. Psychiatry 170, 1114–1133 (2013).

Recent Events and Initiatives

2019 - Ministerial announcement

On National Child Day (November 20), Bill Blair, Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada and to the Minister of Health, announced federal funding to support The Healthy Life Trajectories Initiative (HeLTI), as part of the Government of Canada’s investment into research that improves the health of children so that they can grow into healthy adults who go on to live long and productive lives.

2019 - Data Workshop

Members from all of the successful teams from the Chinese, Indian, South African and Canadian competitions attended a data workshop in September 2017, in Johannesburg, South Africa. The teams developed core approaches to data that will guide data management activities, and also documented roles and responsibilities to ensure that all functions relating to data are clearly articulated, well documented, and conducive to effective review.

2019 - Strengthening Workshop

Members from the teams that were successful at the LOI stage of the HeLTI Linked International Intervention Cohort (LIIC) competitions attended a strengthening workshop. The purpose of this workshop was to assist the successful applicant teams (both Canadian and participating country members) to discuss and agree to a common study design for the intervention cohorts, including approach to and scope of interventions, as well as to agree on overall project governance systems and principles of collaboration.

The HeLTI Approach

The Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) took note of the WHO strategy in designing its Healthy Life Trajectories Initiative (HeLTI) by using the premise of the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) field in its design. This is based on the notion that environmental factors interact with genes during conception, fetal life, infancy and early childhood, when the possibility of modification of an individual’s development in response to environmental conditions is greatest, and that this programming affects the individual’s health later in life. These effects—including developmental delays, cognitive impairment, and chronic diseases—can be observed over several generations. Many environmental factors (such as nutrition, exposure to chemicals or toxins, stress hormones, maternal obesity, diabetes, and general lifestyle) are modifiable, which means that the right interventions can have lasting positive impacts on health.

The Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) took note of the WHO strategy in designing its Healthy Life Trajectories Initiative (HeLTI) by using the premise of the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) field in its design. This is based on the notion that environmental factors interact with genes during conception, fetal life, infancy and early childhood, when the possibility of modification of an individual’s development in response to environmental conditions is greatest, and that this programming affects the individual’s health later in life. These effects—including developmental delays, cognitive impairment, and chronic diseases—can be observed over several generations. Many environmental factors (such as nutrition, exposure to chemicals or toxins, stress hormones, maternal obesity, diabetes, and general lifestyle) are modifiable, which means that the right interventions can have lasting positive impacts on health.

Featured Research

ReACH: Advancing maternal and child health research

Researchers in the DOHaD field study the links between pregnancy, child health, genetics, environmental exposures, and chronic diseases. By identifying the key factors contributing to the development of diseases and intervening at the earliest time possible, the aim is to prevent chronic disease and promote life-long health.